De Beers draws its value from the diamond market. That value has come under scrutiny after last month’s dramatic bid by BHP Billiton to acquire Anglo American, the 85% shareholder of De Beers — a deal Anglo rejected. The offer, along with the diamond market’s weak performance in 2023, has fueled speculation about the future of De Beers.

Anglo confirmed the rumors on May 14, while laying out its strategy to unlock value after rejecting a second offer from BHP. De Beers will “be divested or demerged, to improve strategic flexibility for both De Beers and Anglo American,” the company stated.

The BHP offer seemed to treat diamonds as an afterthought. The proposed deal would have required Anglo to unbundle its 69.7% stake in Kumba Iron Ore and its 79.2% share in Anglo American Platinum (Amplats), the group’s core South African holdings. The country’s regulators would never approve such a deal as it would result in a significant flight of capital out, one financial-services provider explained in informal discussions.

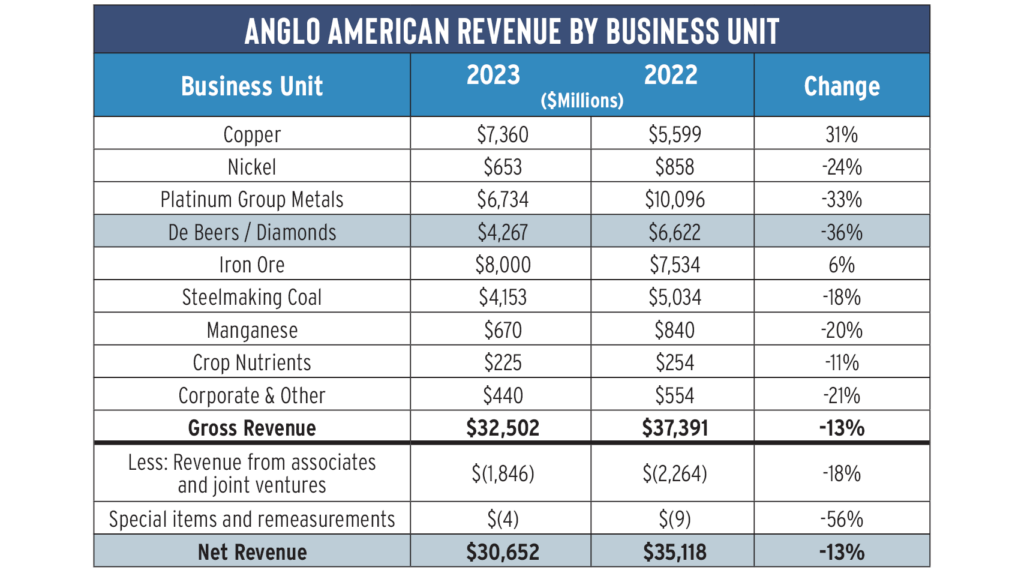

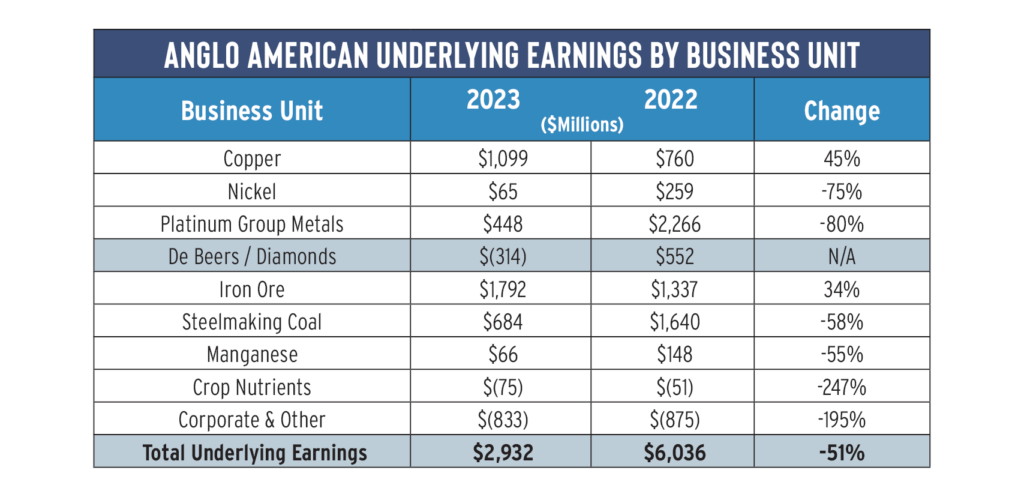

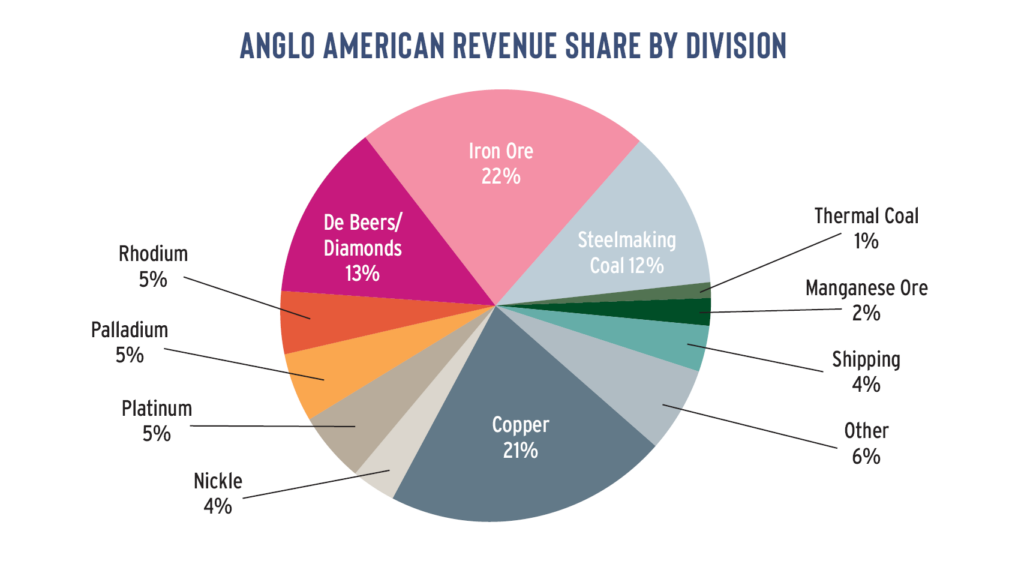

Those stipulations highlighted that BHP is mainly interested in Anglo’s copper assets. Copper showed the strongest sales and earnings growth for the mining company in 2023, accounting for 21% of total revenue (see Figures 1, 2, and 3 below).

While De Beers made the third-largest revenue contribution to Anglo during the year, it ranked among the worst performers in terms of earnings, reflecting the weakness of the global diamond market.

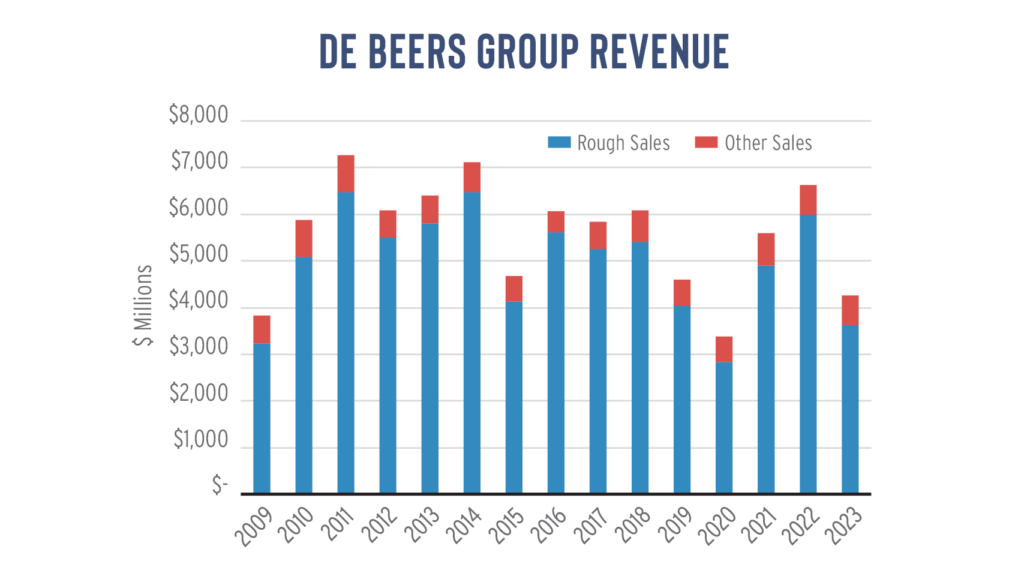

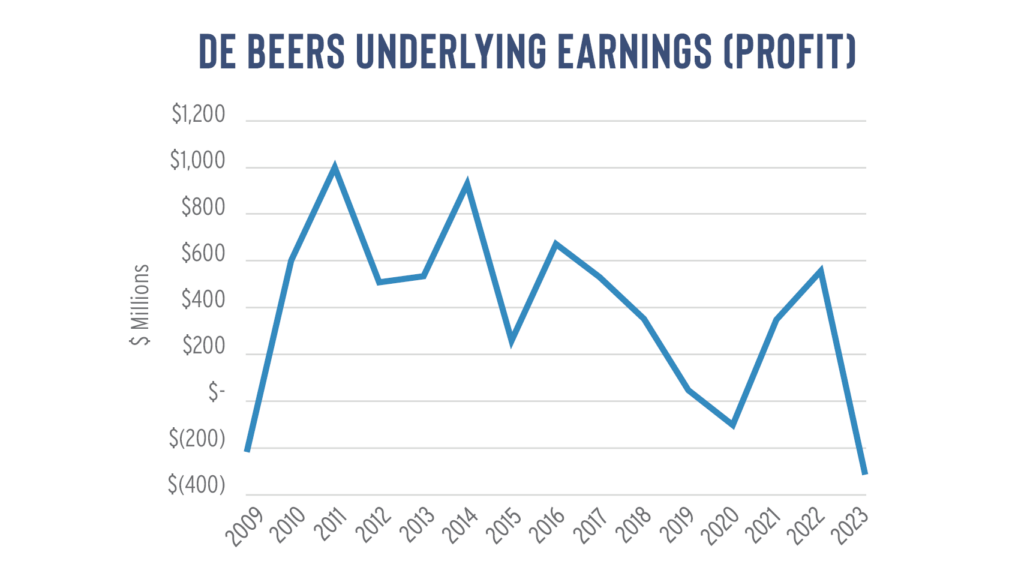

De Beers revenue fell 36% to $4.27 billion (see Figure 4 below), and it posted an underlying loss of $314 million, its weakest showing in more than 15 years — below levels recorded during the Covid-19 crisis and even amid the 2008-09 financial downturn (Figure 5).

The sluggish performance prompted Anglo to write down De Beers’ book value by $1.56 billion in its annual results published on February 22. Since then, a slate of rumors, speculation, and reports that Anglo is considering offloading the diamond giant has flooded the industry. In the latest round, The Wall Street Journal reported that Anglo has held talks with potential buyers for De Beers, including luxury houses and Gulf sovereign wealth funds.

A complex structure

What would they be buying?

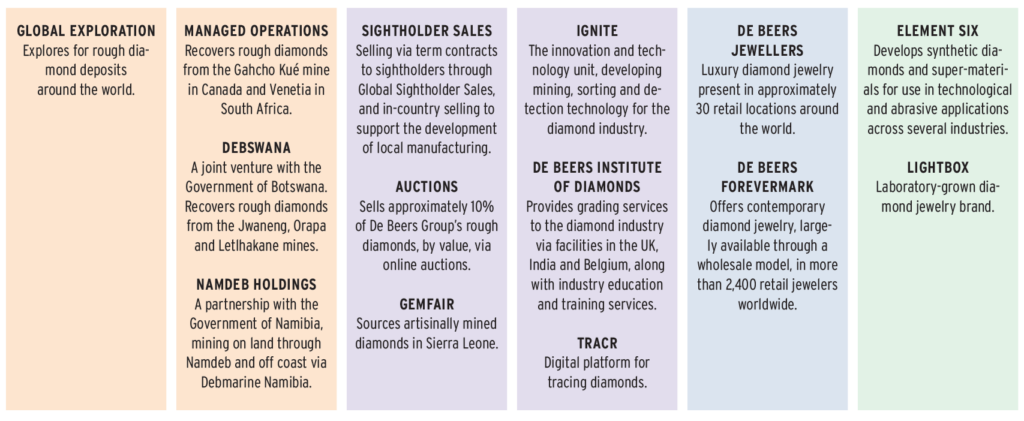

Anglo owns 85% of De Beers, while the Botswana government holds the remaining 15%. Within that structure, De Beers has many aspects to its operations (see infographic).

At retail, it has the upscale De Beers Jewellers stores, and the Forevermark brand which now appears to be focused on the Indian market. The company is involved in mining technology, grading, diamond-equipment development, and traceability solutions through its Tracr platform. It also has a lab-grown diamond brand called Lightbox and Element Six, which produces synthetics and supermaterials for industrial use.

De Beers’ essence, however, is its function as a miner and seller of rough diamonds. The company accounts for an estimated 26% of global rough-production volume, second only to Russia’s Alrosa, while it ranks as the largest supplier by value.

Its rough sales fell 39% to $3.63 billion in 2023, while “other” sales, mainly made up of revenue from Element Six, grew 1% to $639 million (Figure 4 above).

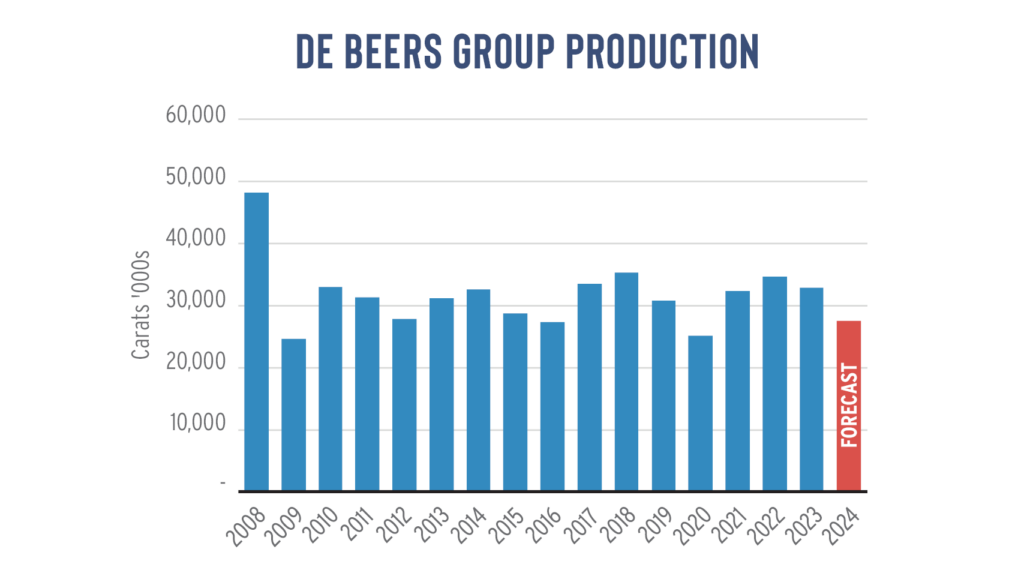

Caution in the rough market has continued into 2024, with De Beers’ rough sales declining 17% in the first three cycles of the calendar year. That, along with some built-up inventory unsold in 2023, prompted the miner to reduce its production outlook for this year. It is now planning to extract between 26 million and 29 million carats, compared with an earlier forecast of 29 million to 32 million carats (see Figure 6 below)

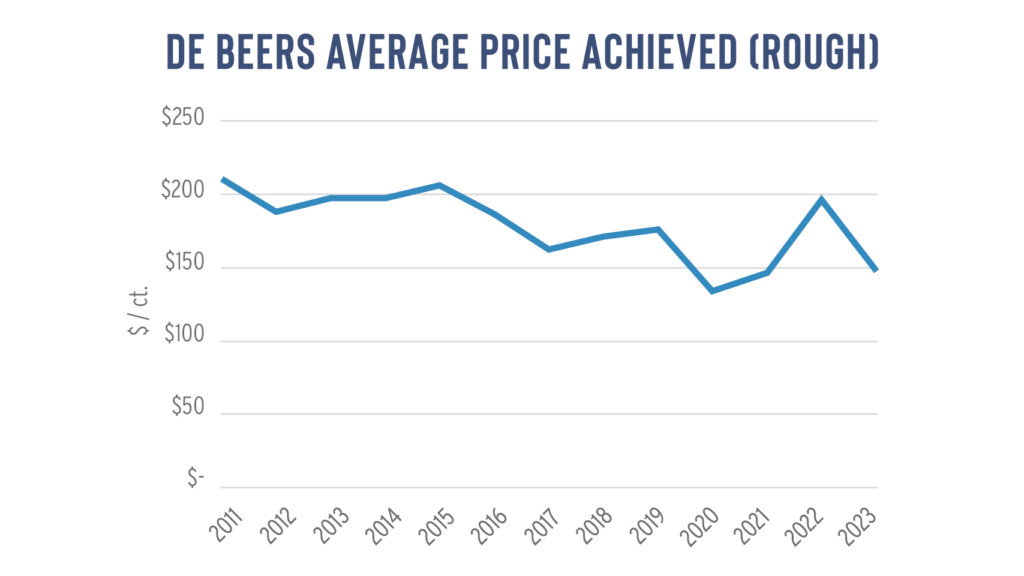

.The frustration for Anglo is that the diamond unit has failed to register consistent growth in the past 15 years. The volatility of its revenue and earnings demonstrates the uncertainty that has engulfed the diamond market during that time. It also shows the loss of the market control De Beers enjoyed over the previous century, and the strategy adjustments the company has had to make.

Exerting influence

Since the 2008-09 financial crisis, the diamond industry has undergone a massive restructuring that has changed the value proposition it offers potential investors.

Such adjustments included requirements to meet higher compliance standards, the emergence of a more efficient distribution chain, the growth of online trading and shopping, shifting consumer habits, the influence of social media, competition from lab-grown diamonds and the ongoing saga relating to sanctions on Russian diamonds.

De Beers has had to adapt to those changes, all while diminishing its role of industry custodian. It ended its singlechannel sales system, sold off some mines, and significantly reduced its category-marketing spend in favor of building its own brand.

However, the company still holds tremendous sway over the diamond market. That is partly due to the high volume of its production and the fact that the rest of the industry clings nostalgically to the De Beers legacy. Sightholders reminisce about the “A Diamond Is Forever” campaigns and even De Beers’ control of supply (and price).

Today, De Beers’ sights — its rough-sales events — still set the tone for the market. A decision by the company to raise or cut prices, or to reduce supply in a weak market, as De Beers did last year, has a ripple effect on the rest of the industry.

As a result, the average price achieved for its rough has also been volatile, arguably providing the strongest indicator of inconsistencies in the diamond market. The price per carat achieved consists of the overall price adjustments made by the company and the mix of goods on offer or in demand.

The average realized price decreased by 25% to $147 per carat in 2023 (see Figure 7 below), as a larger proportion of lower-value rough diamonds were sold, while the average rough price index fell 6%, Anglo reported.

De Beers also continues to exert influence in terms of industry messaging, marketing, and crisis management, even if those initiatives have at times been delayed or reactionary. Its representatives currently hold the chairmanship of the World Diamond Council (WDC) — which speaks for the industry at the Kimberley Process — and the Natural Diamond Council (NDC), an industry-funded marketing organization.

De Beers led the push toward regulatory and financial compliance after the financial crisis and developed its best practice principles (BPP) to which sightholders must adhere.

The company has steered the industry conversation around environmental, social and governance (ESG) issues and was among the first of the majors to highlight the importance of sustainability. Today, its ESG and sustainability initiatives form the basis of the company’s public-relations activity.

The Botswana effect

Significantly, the company has facilitated growth of beneficiation in Botswana and Namibia, by earmarking rough supply for companies with factories in those countries.

It shifted its aggregation, sorting, and sales operations to Gaborone in 2013 and siphoned 15% of Debswana production — the joint venture that oversees its Botswana mining operations — for independent sales by the Botswana parastatal Okavango Diamond Company (ODC).

The proportion of Debswana’s production eligible to be allocated to Okavango has already grown to 25%, and under the recent deal between the government and De Beers it will rise to 50% over the next decade.

As a result, De Beers faces a potential shortfall in its supply, given that Debswana accounts for two-thirds of its group production. But the agreement also presents a challenge for Botswana, through Okavango, to take on some of those traditional roles De Beers naturally assumed.

How Okavango sells and markets its diamonds will have an increasingly important influence on the broader market in the coming years. The company’s recent cooption as a member of the Natural Diamond Council highlights the role Botswana can play in shaping the diamond industry’s narrative.

But it won’t relieve De Beers of its duties, and it doesn’t diminish the importance to De Beers of nurturing its ties with Botswana. Not only would a potential buyer become a partner with the Botswana government, but it would also have to balance its own needs with those of the country’s.

Seeking value

That is something Anglo American has managed with some composure. In the process, the company has committed to massive infrastructure projects, including a $1 billion investment for the expansion of the Jwaneng mine, all with the knowledge that fewer of those diamonds will contribute to its top and bottom line. In addition, the Anglo-owned De Beers is financing up to BWP 10 billion ($725 million) in the newly created Diamond Development Fund (DDF) to facilitate economic upliftment in the country.

Amid De Beers’ complex ownership structure in which the Botswana government owns a 15% stake in the group, as well as 50% of Debswana and 50% of DTC Botswana — which effectively sells the Botswana production to De Beers and Okavango — some 80 cents of every dollar De Beers generates go to the Botswana government.

On paper, Botswana bears greater influence on De Beers than its mere 15% ownership stake suggests. Of course, the country also offers greater value than that, given the scale of its resources.

Anglo inherently understands the sensitivities of the Botswana dynamic given its historic ties to De Beers, and the Oppenheimer family. Times have changed and the Oppenheimers have moved on, having sold their 40% stake in De Beers to Anglo in 2011. But the parent company’s legacy and understanding of diamond market sentiment linger on. It will take some doing for any new owner to replicate.

Indeed, a potential investor in De Beers would signal a new era for the diamond industry. For better or worse, a takeover would finally sever ties to the Oppenheimer-Anglo American past, and possibly empower Botswana to take an even stronger position within the diamond industry.

That would leave the investors with the sole task of creating value for the company, and by default for the diamond market at large. Perhaps it’s the fresh approach the industry needs, given the mammoth changes to which it has struggled to adapt in the past decade and a half. In a potential buyout deal, the challenge would not be finding the right valuation for De Beers but adding value once the ink has dried.

Editor’s note: This article was originally published for subscribers to the Rapaport Research Report on May 7. It has since been adjusted to reflect the confirmation by Anglo American that it plans to divest from De Beers.

Main Image Credit: David Polak & Elisé Jurkovic

Stay up to date by signing up for our diamond and jewelry industry news and analysis.