The Group of Seven (G7) meeting that took place in Japan in mid-May proved to be an anticlimax for the diamond trade.

The industry had expected a major announcement to come from the meeting relating to required declarations on the origin of diamonds imported to those countries — an additional measure that would help prevent polished diamonds sourced from Russian-origin rough entering their markets.

While a clear guideline did not emerge, the member nations — Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, the United Kingdom and the United States — pledged to work toward such measures.

“In order to reduce the revenues that Russia extracts from the export of diamonds, we will continue to restrict the trade in and use of diamonds mined, processed or produced in Russia,” the group said after the meeting.

As it stands, the US and the UK have implemented bans on diamonds sourced directly from Russia. However, the sanctions don’t account for “substantial transformation,” and consequently the manufacturing center is regarded as the source. For example, diamonds polished in Belgium, India, Israel or the United Arab Emirates (UAE) from Russian rough can technically be imported to the US.

Implementing such detailed declarations is proving more complicated than originally thought. Creating such mechanisms will take time, as Feriel Zerouki, the De Beers executive who heads the World Diamond Council (WDC), said in a recent panel discussion at the JCK Las Vegas show in early June. These measures would apply to the entire industry, seemingly requiring a disclosure of origin for all diamonds at customs.

“How do we support the [sanctions] without paralyzing the industry and making it very cumbersome for natural diamonds to enter the G7 countries,” Zerouki challenged the Las Vegas audience.

Setting standards

It’s a sensitive point for an already heavily audited industry, and for companies in each segment of the supply chain that would bear the added expense of verifying such information.

It’s also worth noting that the G7 cannot enact such requirements as a bloc. It will be left to each country to implement its own import rules. That said, there does at least seem to be an effort among those countries to apply some consistency in their systems. It was an open secret that members of various governments and industry bodies met in Las Vegas during the show to advance these discussions, which presumably covered a wide spectrum of industry-related issues.

Central to the talks must surely be the practicality of such declarations. What mechanisms are available to the industry that would facilitate traceability? And who verifies that these initiatives meet the required standards? And on what are those standards based?

The trade has at its disposal industry structures as well as company programs that tackle the challenge of traceability and source verification — although arguably nothing is foolproof.

The Industry track

At an industry level, the parties can’t rely on the Kimberley Process (KP) to deal with the Russia issue due to its narrow definition of conflict diamonds, which relates to rebel groups using diamonds to fund civil war. The KP doesn’t account for human-rights violations such as those being carried out in Ukraine. It still counts Russia among its members.

The WDC’s System of Warranties (SoW) is a tool through which companies can include a warranty statement on invoices assuring that the diamond originates from sources compliant with the KP. The WDC recently updated the SoW to include business practices pertaining to human and labor rights, anti-money laundering and anti-corruption.

While there is a registration process and annual renewal to participate in the SoWs, they rely heavily on trust that the supplier is meeting the stated standards, with that adherence based on a self-assessment mechanism.

As far as organizations are concerned, the trade mostly relies on the Responsible Jewellery Council (RJC) for direction on the Russia issue.

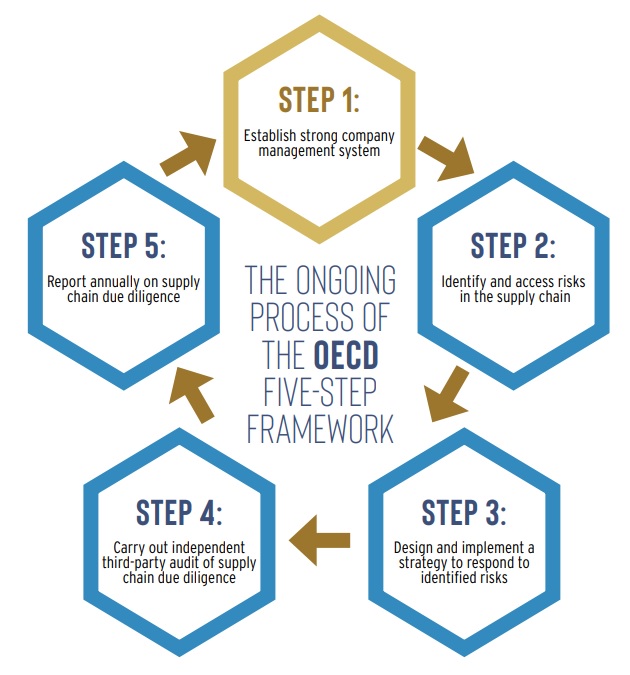

RJC chairman, David Bouffard, who is also vice president of corporate affairs at Signet Jewelers, the largest retail jeweler in the US, points to the due-diligence standards for responsible sourcing of minerals of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). These provide detailed recommendations to help companies respect human rights and avoid contributing to conflict through their mineral purchasing decisions and practices, the OECD explains on its website.

Both the RJC and Signet built their strategies regarding Russian supply around them, Bouffard said. The guidelines are a five-step process providing a framework for companies to determine human-rights risks in their supply chains (see infographic).

When the war in Ukraine began on February 24, Signet applied the five steps to determine “that this is a human-rights risk in our supply chain that we don’t want,” Bouffard explained at the Rapaport Social Responsibility conference in Las Vegas in June.

Signet cut ties with Alrosa when the war broke out, and it worked with its suppliers to implement its ban on Russian-origin goods, he noted, adding that RJC members were compelled to follow the same guidelines.

“If you work with the OECD guidelines it’s an easy answer,” he stressed. “There are human-rights violations on an extraordinary scale [in Ukraine], and if a company looks at its supply chain and has human-rights abuses as a risk, then it’s an easy solution as to what to do — and that is to not carry Russian diamonds.”

He advocates a four-tiered approach for diamond and jewelry companies navigating this complicated landscape: begin with the KP, then incorporate the WDC’s SoWs, followed by RJC membership, and then apply Signet’s Responsible Sourcing Protocols — an open-source system Signet developed as a guide on how to acquire product. However, the challenge for the RJC, the primary standards-setting organization for the industry, is how to implement a ban, since its role is to set standards, not police the industry, Bouffard acknowledged.

Follow the law

Consequently, all the RJC can do is to advise companies to follow the laws of their respective lands, Bouffard clarified. US companies are subject to the strictest laws when it comes to Russia, as it is the only country with a full set of sanctions targeting the people (Alrosa’s management), the company (Alrosa), and the product, Bouffard said.

But RJC members are subject to a spectrum of laws depending on their jurisdiction. While its members have committed to following the OECD guidelines, the RJC cannot suspend them unless a company has violated their country’s law.

The industry is therefore governed by different standards, according to the regulations in which a company operates. A manufacturer whose government allows it to trade Russian diamonds may choose to segregate its supply. As an RJC member, it could pledge not to supply Russian-origin diamonds to members for whom they are banned and earmark those goods for countries where they are legal.

Participating in the Rapaport Social Responsibility conference in Las Vegas were Iris Van der Veken (left), David Block, and David Bouffard. (Rapaport News)

Value judgment

It is therefore left to the individual company and its leadership to decide its vision, argued Iris Van der Veken, CEO of the Watch & Jewellery Initiative, an industry think tank on sustainability and responsible sourcing. In addition to the OECD guidelines, Van der Veken highlighted the United Nations Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights as an instrument to help companies develop their responsible-sourcing practices. Whatever that “value decision” might be, she urged companies to be honest and transparent about their supply.

“When you segregate those diamonds, you need to be very clear on it, but that’s when it becomes challenging,” she pointed out. “When companies start to say they are bringing in Russian diamonds to the supply chain, potentially not allowed in certain countries, that might infringe on the trust of the entire industry.”

Indeed, none in the industry has openly admitted to buying Russian rough since the war broke, although Alrosa has continued to supply. Imports to Belgium and India combined fell just 3% by value and the same margin in volume terms in the two months of 2023, versus the comparative prewar period last year. One diplomat asserted that Alrosa has been able to continue to sell all of its production in recent months.

Rough to polished

Manufacturers may be segmenting their Russian goods. But the industry therefore cannot rely on companies’ willingness to disclose the source of all of their supply, even if they’re RJC members. That invites the question whether science and technology can determine and assure a diamond’s origin.

There is no scientifically robust study that demonstrates the unique and measurable characteristics that would allow for independent provenance determination of a random individual diamond, a paper by Evan Smith, a researcher at the Gemological Institute of America (GIA), found.

“Unfortunately, the ideal goal of determining origin independently through a lab analysis is not on the horizon,” Smith wrote in his summary. “For now, and the foreseeable future, the only definitive method to establish diamond origin depends on retaining country-of-origin and/or mine-of-origin information from the time of mining.”

With that in mind, the GIA developed its Diamond Origin Reports, whereby it analyzes rough before undergoing polishing, so that there is a link between the polished and rough stones, enabling source verification along the diamond’s journey.

That process requires the institute to partner with miners or manufacturers to supply rough for the program. Some are put off by logistics, as the process adds another layer to getting the diamond to market.

The GIA recently forged a cooperation with Botswana parastatal Okavango Diamond Company to analyze its rough. The resulting polished will be marked on the RapNet trading platform with a Green Star designation, Rapaport’s recently launched program verifying that a stone was ethically sourced. Tom Moses, the GIA’s executive vice president, said the organization would return the goods to Okavango within three days.

Geneva-based Spacecode claims to be developing an affordable artificial intelligence (AI)-driven technology that will be able to fingerprint every diamond from 0.20- to 50-carat sizes, Ari Epstein, CEO of the Antwerp World Diamond Centre (AWDC), wrote in a letter to the trade.

“Yesterday we thought that identifying the origin with spectroscopy was still seven years away,” he said. “Today it can be done in less than two years and probably even faster, with devices delivered to market in 2024.”

Such a scientific approach would bring another layer to the debate, and perhaps combine well with the industry programs to clarify their provenance claims. But the science is yet to be proven, and at least from the GIA’s perspective, it will be difficult to implement. Tech-based solutions are more accessible at this stage.

Origin suite

De Beers has taken a different approach by tackling traceability through its Tracr blockchain. The company opened Tracr to the broader industry in June during the Las Vegas shows, after it originally focused only on De Beers production.

Tracr generates a unique digital fingerprint for each diamond, allowing them to be traced through every stage of the process along the supply chain, creating a trail of transactions as the diamond changes hands or form.

But De Beers contends the idea is to transcend the focus on provenance. Rather, the point is the story of the diamond, Marc Jacheet, CEO of De Beers brands, emphasized in an interview. To leverage that idea, the company also unveiled its Origin suite of services — a marketing program powered by its grading division, De Beers Institute of Diamonds, built around De Beers goods that are on Tracr.

The suite includes new origin and grading reports and a digital search that connects clients with the origin and impact of their diamond, the company explained in a press release. De Beers will also launch Origin Story — slated for the first quarter of 2024 — as a tool that retailers can use to enhance their storytelling around their De Beers supply.

In developing the concept, De Beers identified four trends that are driving consumer habits, Jacheet explains: the growing importance of brands, client-centricity and creating an immersive customer experience, digital savviness and appropriateness, and a sense of purpose. Retail jewelers working with Origin Story will be able to tap each of those elements, he says, including an understanding of the positive impact their diamond has made on society.

On a journey

Sarine Technologies has also adopted a two-pronged approach, focusing on the process of tracing the diamond and enabling the storytelling element for retailers. It is working with select miners to scan the rough at the mine site, and with cutters who are using Sarine equipment in their factories to scan the goods through the manufacturing process.

Its competitive edge, the company claims, is that it has control over the input of data through its systems on site. In the manufacturing process, there are four compulsory stages of scanning the diamonds, which give a high probability of matching the diamond through the value chain, Sarine CEO David Block asserts.

At the mine, Sarine is able to scan 2-carat rough and above. Smaller goods become more cumbersome and time consuming to register at the mine, although Block is confident the company can get it down to 0.50 carat rough, translating to around 0.20-carat polished — “which is good enough,” he says.

Block did not disclose the number of diamonds that have gone through Sarine’s Journey program, saying only that it’s in the hundreds of thousands. De Beers has over 1.2 million stones registered on Tracr. Block recognizes that at this stage, the industry needs to create a larger pool of people using these provenance programs — across all platforms — for them to gain traction.

From a marketing perspective, Sarine is pitching its tool from two angles, he explains. One is to verify the information for the consumer, presenting a variety of information about the diamond journey in many ways, be it through Sarine’s physical reports, its digital ones, or even as a 3D print of the rough diamond from which the consumer’s polished stone comes. Sarine provides marketing material, but it is ultimately left to the retailer to decide how it wants to use the Sarine Journey program to tell the story of the diamond.

Another way is for internal purposes where Sarine is working with brands to back up their provenance claims. That idea could be useful for an industry-wide application – be it powered by Sarine, Tracr or any other program.

Tech, science and disclosure

In formulating its strategy, the G7 should take note of the technology and science these programs represent. Other initiatives, such as Spacecode and iTraceiT are providing the technology and leaving the marketing elements to their users. Belgium-based iTraceiT has built a blockchain facility and is using QR codes to track diamonds. It claims to be able to do so for all sizes, including melee, which has proven to be a stumbling block for other systems.

Whichever mechanism is in place, perhaps these industry players can step up to help governments in their efforts to build more robust origin disclosures at the customs level.

One assumes the G7 is considering all these options while working on its measures. Would participation in any of the programs mentioned be enough to pass the respective customs inspections? The AWDC’s Epstein hinted at an ideal scenario whereby science would indeed provide the capabilities to verify the rough origin of a polished diamond, as he endorsed Spacecode’s program.

“Suddenly, traceability will need to take a back seat because qualified origin can be determined with ease, and at an affordable rate, at the end of the value chain,” he asserted. “There will be no need for declarations or endless paperwork, and there won’t be any loopholes to be used, as a simple test will tell you all the consumer needs to know.”

“Governments will quickly adopt and embrace this kind of technology, and more importantly, it will create a more equal level playing field that eradicates rubber stamping and greenwashing,” he added.

For now, there is insufficient public evidence to suggest that such capabilities work, and it’s not clear they would be robust enough to inspire governments to rely on them solely. Regardless of the G7’s pending directive, it is left to the trade to make transparent and robust claims about the origin of its diamonds.

Historically, the diamond industry has relied too heavily on trust in its business practices, and to a large extent it continues to do the same regarding responsible sourcing. The trade must embrace the technology that’s available to prove the origin of its diamonds. By doing so, the industry will not only tell a better story, but protect its reputation and ensure a value-driven pipeline untainted by conflict or human-rights abuses.

Main image: Students at the Mokobaxane Primary School in Orapa, Botswana. De Beers is highlighting the impact that diamonds have on communities in its origin Story program. (De Beers)