The diamond market has yet to feel the full effect of the war in Ukraine. Initial predictions pointed to a potential supply shortage that would result from having Alrosa, with its large share of global rough production, off the market. However, those scarcities have not emerged significantly.

This might be because the industry is still adjusting to the impact of US sanctions placed on Alrosa as the world will mark the one-year anniversary of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine on February 24. We recognize three areas in which the trade was, or will be, affected:

- A slowdown in demand as the war fuels global economic uncertainty;

- The decline in rough-diamond supply due to US sanctions on Alrosa;

- A bifurcation of the market as the industry splits into two streams, between ethically sourced diamonds and those that are not.

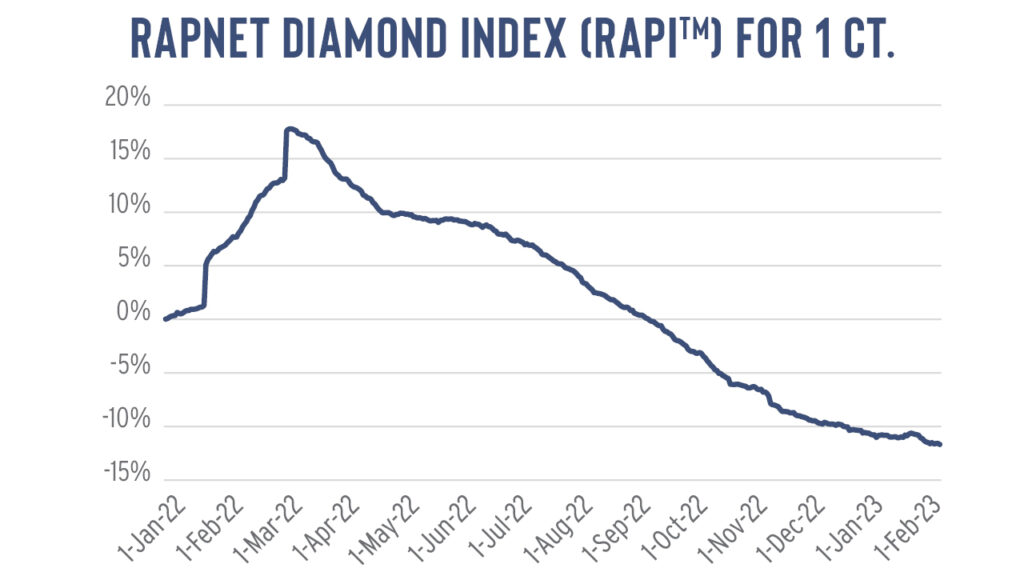

Among those factors, the industry most acutely felt the impact of the war on global demand in 2022. Trading slowed because of that event, along with the economic uncertainty already in play, with the conflict fueling high inflation. Polished prices peaked a week after the invasion and have been on a downtrend since (see graph below).

The effect of the war on global economic growth is tapering off. The outlook for the US remains cautious due to continued inflation, higher interest rates and the inevitable drop-off from the strong recovery following the pandemic.

Meanwhile there is some optimism for a rebound in China since the government opened its borders after lifting its zero-Covid policy.

While that all plays out, the trade is now focusing on the second and third factors tied to Russia, which didn’t fully exert their influence in 2022. Those relate to how sanctions on Alrosa will affect supply and push the market toward showcasing its responsible-sourcing credentials.

This report is the first in a three-part series that Rapaport will publish about the diamond industry’s Russia crisis. In this installment we aim to understand Alrosa’s position in the market and the repercussions of the largest producer being excluded from the mainstream pipeline. Part two will focus on the sanctions and what they really mean for the industry. The third report will project what a split market might look like, outlining the industry’s options for tracing its supply and providing assurances to consumers that their diamonds are ethically and legally sourced.

A fox in a hole

Legend has it that a fox led geologists to the site where the first diamonds were found in Russia’s Yakutia Republic. More accurately, after recognizing a similar geological landscape to that of South Africa’s kimberlite ore formations, geologists in post-World War II Russia descended on Yakutia, a vast 1.2 million square-mile territory about 3,000 miles east of Moscow, scrutinizing the banks of the Vilyuy River for volcanic pipes. By the spring of 1955, geologist Yuri Khabardin was excited to come across a foxhole in a ravine that exposed blue earth, indicating high diamond content. (See “Alrosa the Diamond Fox” in the July 2013 issue of Rapaport Magazine).

Much was at stake, with the directive to find diamonds coming from the highest levels. Joseph Stalin recognized the need for industrial diamonds to help rebuild Russia after the war, and he knew he couldn’t rely on De Beers goods for fear they might boycott supply to the Soviet Union.

From that initial discovery of the Mir mine, Yakutia emerged as arguably the most diamondiferous region in the world. With its immense resource, the Russian government agreed to sell its production through De Beers, which enabled the then-South African miner to maintain its control of the diamond market.

While the volume of goods sold to De Beers varied over the years, the arrangement was terminated only in 2009 after the European Commission ruled the arrangement breached its competition laws.

That set Alrosa on a new path toward independence and influence in the diamond market. With an initial public offering (IPO) in sight, the company began offloading its noncore subsidiaries, which included oil, gas iron ore, hydropower, banking, aviation and hotel units. By the time of its listing in 2013, the company was focused on leveraging its rough-diamond production volume to spur growth.

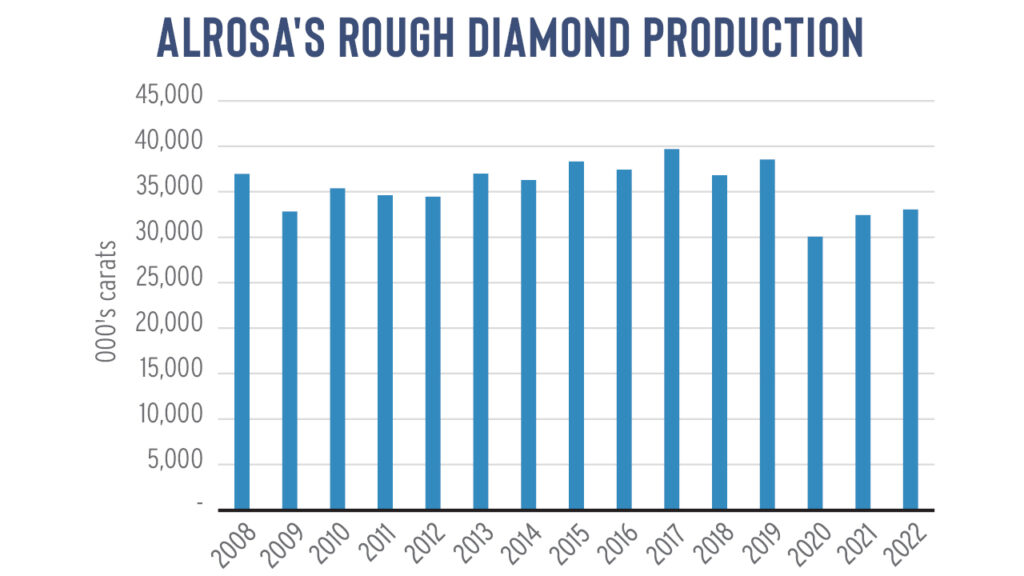

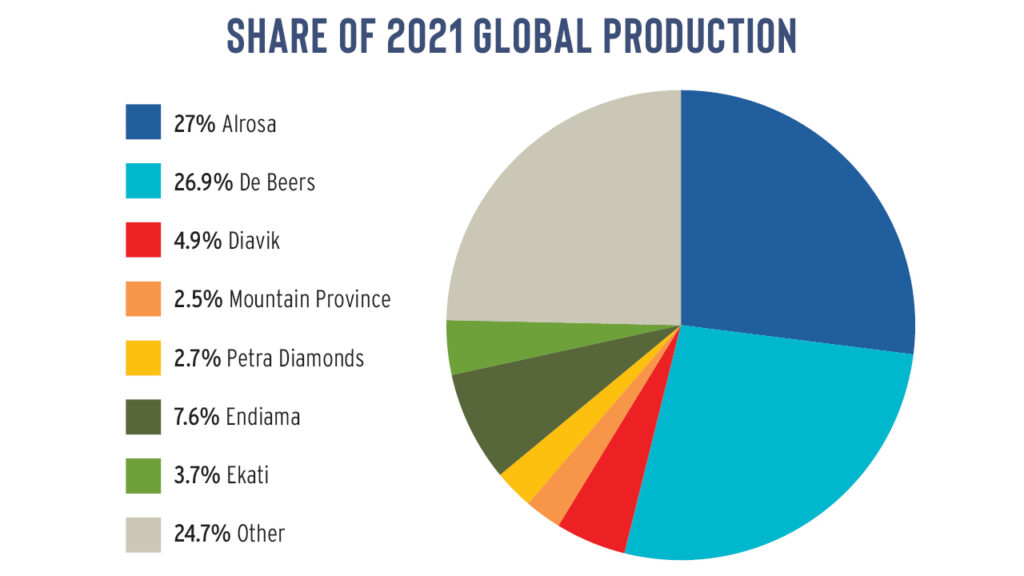

While De Beers had shifted focus to branding, Alrosa was building its credentials as the largest volume producer of rough diamonds. It recovered an average of around 35 million carats a year in the past decade (see graph), and although that dropped a bit in recent years, Alrosa was still the largest volume producer in 2021 — just above De Beers (see chart). Alrosa had projected production of 33 million to 34 million carats for 2022, though it hasn’t published its results since the onset of the war.

The company has some 20 mines across five divisions, including Aikhal, Mirny, Udachny, Nyurba, and Lomonosov (Severalmaz) carrying an impressive resource of over 1 billion carats, according to its website. Those consist of a mix of kimberlite, alluvial and tailings operations, while Alrosa has invested heavily to go deeper with underground mining at the famed International, Aikhal and Udachny operations. A flood at the Mir underground mine in 2017 forced its closure, with reconstruction expected to begin in 2024.

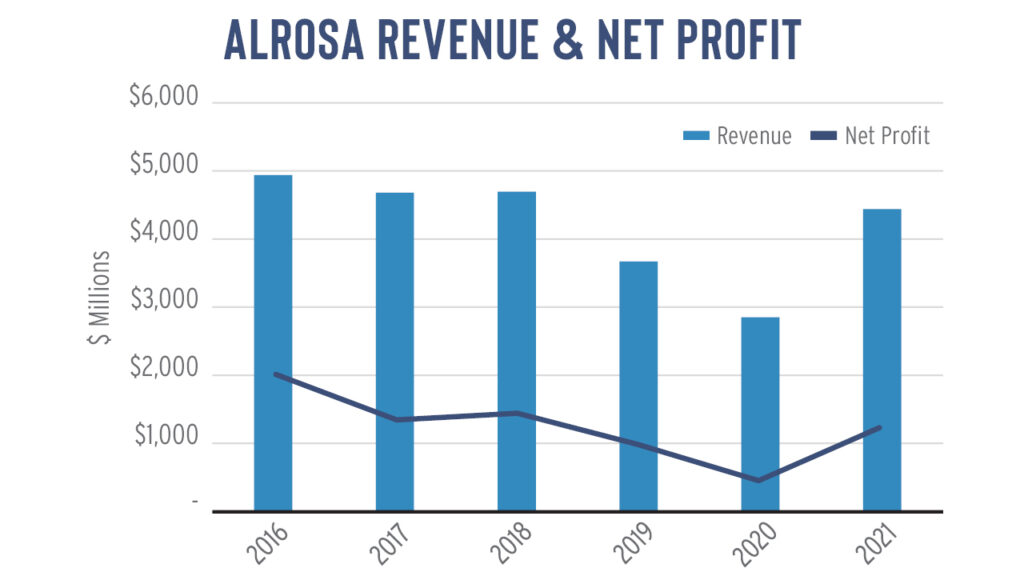

The company has enjoyed steady growth over the past decade. Revenue jumped 51% to RUB 326.97 billion ($2.99 billion) in 2021, spurred by the recovery from Covid-19, while net profit grew to RUB 91.32 billion ($834 million), almost triple 2020’s figure of RUB 32.25 billion ($297.3 million) (see graph).

exchange rate for each year.

Approximately 70% of sales are made to contract clients at monthly events through the Alrosa Alliance program, similar to De Beers’ sight system, while it also holds regular auctions and tenders as well as spot sales to individual clients. Its sales gradually became a barometer for the trade in a similar — though arguably less influential — manner to the De Beers sights.

Opening up

The October 2013 IPO gave the company a market capitalization of $8.12 billion. More importantly for the industry, it forced the miner — which was previously seen as secretive — to become more transparent as it now had a broader range of shareholders to whom to answer and had to meet the reporting requirements of the Moscow Stock Exchange.

In its current shareholder structure it is 33% owned by the Russian Federation, 25% by the Republic of Yakutia, 8% held by the local Yakutia municipalities, and 33% traded on public markets. The transparency drive brought informative quarterly trading updates, earnings reports, monthly sales disclosures, and open dialogue about its operations.

Management also made a concerted effort to engage with the industry, taking central roles in organizations such as the World Diamond Council (WDC), Responsible Jewellery Council (RJC), Diamonds Do Good (DDG), and the Natural Diamond Council (NDC), among others.

In addition, it stepped up to its role as a responsible company, contributing to local community projects, and embracing environmental, social and governance (ESG) issues surrounding its operations.

In a slight deviation from its production-centric approach, the miner also began diversifying its portfolio, building up a sizable polishing division that was boosted by its acquisition of Kristall of Smolensk in 2019. It started using its polished unit as a platform to build some brand equity of its own, with initiatives such as the Romanov collection and its more recent efforts to promote diamonds with fluorescence, since its production contains a higher-than-average percentage of these goods.

The company targeted the US, the largest consumer market for diamond jewelry, to elevate its position as an important, ethical, and diverse diamond producer.

The devil is in the data

Those marketing programs and the company’s involvement in industry affairs came to a halt when the war broke out last February — in some cases in controversial fashion. It also stopped publishing reports about its sales and operations.

That has left a gap, making it more difficult to assess global production, rough sales and how they relate to the market. The miner reportedly changed its Alrosa Alliance client list recently, with more secrecy regarding who it includes. Very few admit they continue to buy rough from the company. And if they are purchasing, it is also unclear how they are paying, given that Russia has been blocked by most international transfer systems.

US sanctions on Alrosa and the restrictions placed on international money channels to Russia limited access to the world’s largest producer of rough diamonds. But the sanctions have loopholes and are being revised. They restricted only direct imports from Russia but allowed orders of diamonds sourced in Russia yet polished in other centers. (We will examine in greater depth the mechanics of the sanctions in the next instalment).

In addition, other countries have not imposed sanctions — notably Belgium, the largest prewar trading center of Alrosa diamonds; India which typically manufactures them; and Dubai, which facilitates their trade to India. Russian goods still have a path to market, and they are clearly filtering through.

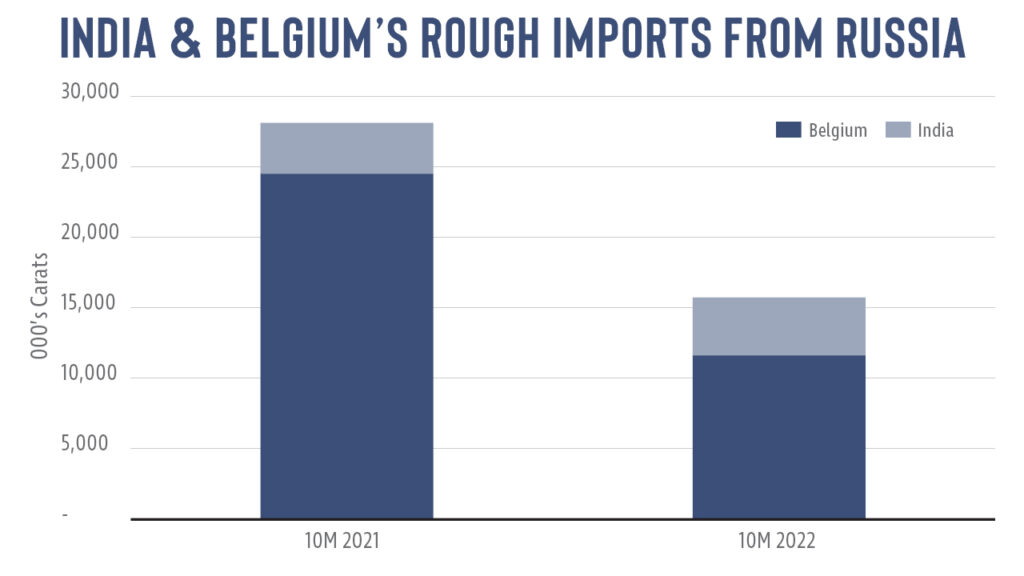

Data from the National Bank of Belgium suggest that country’s imports of nonindustrial rough diamonds from Russia fell 8% year on year to EUR 1.26 billion ($1.35 billion) in the first 10 months of 2022, and by 53% in volume terms to 11.6 million carats.

Meanwhile, statistics from India’s Ministry of Commerce suggest its nonindustrial rough imports from Russia rose 23% by value to $902 million during the same 10-month period, while by volume they increased 14% to 4.1 million carats. India’s Gem & Jewellery Export Promotion Council (GJEPC), which tracks its own data based on the ministry’s, did not respond to Rapaport’s request to explain the increase by press time.

It is likely that some of the goods lost to Antwerp are being sent direct to Surat, whereas they would typically stop in Belgium en route to India even in a normal market. The combined imports from Russia for the two centers fell 44% year on year to 15.7 million carats (see graph) for the period January to October. Import data by source country was not available from other major rough-trading centers — notably Dubai, Israel and China.

The bigger test

Either way, Russian diamonds are clearly entering the market, and Alrosa appears active. And assuming they’re not going to the US, considering the legal and reputation implications of dealing in these goods, there are other destinations that don’t have the same concerns — namely China and India.

While there are retail outlets in these non-American markets to which suppliers can sell, the greater challenge is for dealers and manufacturers to ensure that Russian and non-Russian diamonds don’t mix in the trading, cutting and polishing stages. Can the trade give US jewelers the assurances they seek that their supply is not from a banned source? Can it trace its supply to facilitate the full ESG story that luxury brands and jewelers need to tell?

That will be the big challenge for the diamond industry in 2023 as the Russia crisis lingers. Alrosa supply will likely increase this year. The trade will need to decide how best to disclose these goods.

Correction, February 22, 2023: Belgium’s rough imports from Russia fell 53% by volume to 11.6 million carats in the first 10 months of 2022, and not 29% to 2.6 million carats as initially reported in this article. The combined imports of Russian rough to Belgium and India amounted to 15.7 million carats during the same period, down 44% by volume from the previous year, and not as stated previously.

This article first appeared in the February edition of the Rapaport Research Report. Subscribe here.

Image: Rough diamonds recovered by Alrosa. (Alrosa)