From the war in Ukraine to traceability efforts and the NFT revolution, here’s a rundown of events that shaped the industry in the last 12 months.

The Russian disruption

As Russian tanks began rolling into Ukraine on February 24, major jewelers and retailers around the world announced that they would no longer sell Russian diamonds. The response from trade organizations, however, was slow and muddled. Diamond giant Alrosa, which is partly owned by the Russian government, stepped down from the Natural Diamond Council (NDC) on March 4 and suspended its membership in the Responsible Jewellery Council (RJC) on April 1. Neither group condemned the invasion. It was a silence that many industry members considered deafening — so much so that Cartier, Kering, and several other major houses left the RJC to form the Watch & Jewellery Initiative 2030.

Europe’s response was even less clear. No sanctions are currently in place against Russian diamonds. Indeed, Antwerp-based diamantaires lobbied to keep trading the Russian gems to avoid losing their business to Dubai.

In June, Alrosa defiantly announced that it would maintain its original 2022 production forecast of 34 million to 35 million carats — more than its 2021 output of 32.4 million carats. Some diamond experts expect non-Russian goods to appreciate in price and the supply chain of diamonds to bifurcate into two streams: non-Russian diamonds flowing into Western brands, and Russian ones going to Asia.

The reality, however, is opaque.

In Antwerp, diamond dealers whisper that Alrosa is selling its stones below market value to tempt dealers into mixing them with gems from other countries. One way or another, diamond prices in general have been lower than usual, whether because of Russians underselling their stones or because of depressed demand in China.

Crypto and digital data

Over the last two years, non-fungible tokens (NFTs) have taken the luxury market by storm. In March 2021, digital artist Mike Winkelmann — aka Beeple — sold his NFT Everydays: The First 5,000 Days for $69.3 million at Christie’s. In September of that year, Dolce & Gabbana partnered with digital luxury marketplace UNXD to create nine NFTs that sold for a total of 1,885.72 ether — the cryptocurrency used on the Ethereum platform — or nearly $5.7 million, per the going exchange rate.

This past August, Tiffany & Co. launched and quickly sold out a collection of 250 custom gem-encrusted pendants for holders of CryptoPunks NFTs, dubbing the pieces “NFTiffs” and linking them to digital versions of themselves. At 30 ether each — around $50,000 — the collection netted about $12.5 million in total.

But NFTs can be good for more than just making a quick buck. Companies can embed the data of a stone’s physical journey in an NFT and sell it together with the diamond as an enhanced certification. People who own diamond jewelry with NFT equivalents can wear the digital versions in the metaverse, or incorporate them into character skins when playing video games.

The Gemological Institute of America (GIA) is going full steam ahead with digital. In June, it announced plans to phase out paper reports and release solely digital ones by 2025. From now on, the lab will pair graded stones with a QR code and a serial number, which clients can use to view the report in the GIA database. They can then save the report in their Apple Wallets.

The downside to all this is that hackers are increasingly targeting digital data. This summer, it emerged that London-based jeweler Graff had paid $7.5 million in digital currency to a Russian gang to prevent it from leaking hacked data on the jeweler’s clients.

Are lab-grown stones shining brighter?

This year, watch brand TAG Heuer used lab-grown diamonds for the first time. In the Carrera Plasma model, which the LVMH-owned company unveiled during Watches and Wonders in April, lab-grown diamonds formed the case, dial and crown. CEO Frédéric Arnault quickly pointed out that the move was not intended as an opening to lab-grown diamonds per se, but to their potential use in crafting innovative shapes. Obviously, that same watch with natural diamonds would have cost many times the current $376,000 price tag, likely making it commercially unviable.

Among other things, the move begged the question of whether the Ukraine conflict, which has put Russian diamonds off-limits, could be a chance for lab-grown diamonds to shine.

Lab-created diamonds have been on the rise for some time already. In October 2021, industry analyst Paul Zimnisky calculated that synthetics producers had put out nearly 3 million carats so far that year — a colossal figure compared to the few hundred thousand carats coming out annually only a few years earlier, but still minuscule next to the 116 million carats of natural diamonds mined in 2021.

Jewelry brands using lab-grown have ballooned, marketing themselves as more ethical and sustainable than their natural counterparts. While these claims are often exaggerated, they have nonetheless changed perceptions. If lab-grown was once tantamount to “fake,” it now stands for “green.” Swiss watchmaker Breitling jumped on the bandwagon in October, announcing plans to phase out natural stones by the end of 2024 in a pledge to be “more sustainable.” It’s worth noting that the Indian facility producing Breitling’s diamonds is not carbon-neutral. However, for every lab-grown carat the company sells, it has pledged to contribute to a social impact fund for diamond-producing communities, which would otherwise depend on the natural-diamond industry for their livelihoods.

Perhaps the most significant statement in favor of synthetic diamonds comes from LVMH, which acquired a stake in Israeli lab-grown producer Lusix. The luxury giant pointed to the high quality of Lusix’s stones and the growth potential of the company as reasons for its investment. Moreover, Lusix presents its gems as a golden sustainability standard, since the facilities run exclusively on solar power.

Covid-19: A tale of two worlds

While much of the West has become accustomed to living with Covid-19, China has maintained its zero-Covid policy. As a result, outbreaks mean citizens must still endure lockdowns, and travelers have to quarantine. This has taken a toll on the Chinese economy. “China’s gross domestic product (GDP) growth is expected to slow sharply to 2.8% in 2022, from 8.1% in 2021,” wrote the World Bank in September. As such, Chinese interest in luxury is down. The country’s polished-diamond demand fell by a mid-single-digit percentage year on year for 2022’s first half, according to the latest De Beers Diamond Insight Report.

In other global markets, however, the fiscal stimulus during the pandemic helped the diamond business build momentum. “Global demand for natural diamond jewelry grew by an estimated high-single-digit figure in the first half of 2022 compared with the first half of 2021,” the report says. China’s Covid-19 restrictions forced September’s Jewellery & Gem World show to relocate temporarily from Hong Kong to Singapore. In contrast, JCK Las Vegas resumed as scheduled in June.

Of course, even if Western customers have returned to physical stores, they have not unlearned the habit of shopping online. In 2015, only a third of all natural-diamond purchases included a digital element, but today, this accounts for half of them.

Jewelers reconnect with the Earth

Place Vendôme jewelers that are holding to natural diamonds are strengthening their ties to the mines in order to increase traceability and highlight the social impact on local communities.

Van Cleef & Arpels’s latest high-jewelry collection, Legends of Diamonds, comprises 25 pieces featuring diamonds that all originated from the same rough stone: the 910-carat Lesotho Legend, which the maison bought a few years ago.

Messika has gone a similar route, using 15 diamonds from a single large rough to craft its Egyptian-style Akh-Ba-Ka high-jewelry set.

Such ventures show that the mine-to-market approach is in full swing. Houses such as Tiffany & Co., Harry Winston and Louis Vuitton have recently pumped considerable resources into establishing closer relationships with diamond mines. Tiffany pioneered this trend about 20 years ago when it struck a deal with Canadian miner Aber Resources. More recently, Louis Vuitton partnered with manufacturer HB Antwerp and Lucara Diamond Corp. to market the large Sewelô and Sethunya rough diamonds, both from Lucara’s Karowe mine in Botswana.

Brands are also trying to enhance their traceability tools. De Beers, for instance, is launching a series of improvements on its Tracr technology, while the Richemont- and LVMH-backed Aura Blockchain Consortium is taking on new product categories.

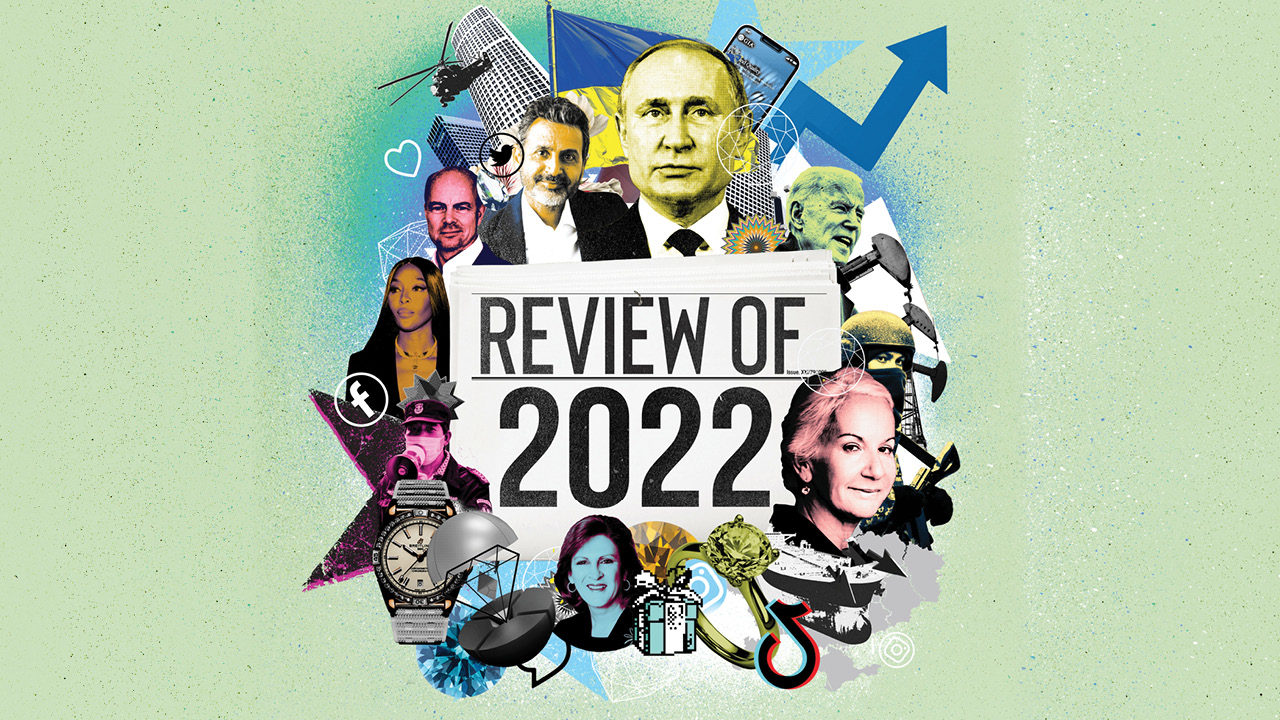

Image: A bespoke digital collage created for Rapaport Magazine to capture the diamond industry in 2022. (Illustrator: Steve Rawlings; Agency: Debut Art)