There’s anticipation in the air as two young miners follow their sorting supervisor into a tin-roofed structure atop a mound at the Baken mine. A sign at the entrance announces the space as the “Communal Artisanal Miners Diamond Jig Sorting House,” which is another way to signal the end of the recovery process — where the miners receive the results of their day’s labor.

Don’t be fooled by the simplicity of the room, suggests supervisor David Venter, a tall, well-spoken veteran diamond miner, with his deep voice and a hint of a smile. Inside, the paneled walls are decorated with just two posters — a satellite image of Baken and a “Guide to dangerous snakes” — but there are security cameras all around the room, he shares.

Another man overturns a pizza-shaped sieve onto a table, removing the gauze that reveals the washed-out gravel for the miners to sort through, the last remaining heap of stones from their mining efforts that may contain their coveted diamond. After just a few minutes of careful sifting, it’s clear this lot did not contain the riches they sought.

“It’s like a lucky packet here; you just don’t know what you’re going to get,” Venter says. “The biggest diamond we’ve found here was an 18-carat stone, but you can also go for a while without finding anything.”

The important part is to have the miners present throughout the process, explains Marius Coetzee, general manager at Lower Orange River Diamonds (LOR), which owns the Baken mine. The diggers need the assurance they’re not being cheated out of a potential windfall, so they follow the ore they’ve dug from the pit through to the jig, where it is washed and processed, and finally to the sorting house. And if they find a stone, they’re paid an estimated sum immediately and topped up if it exceeds that price when it’s sold at tender.

RELATED READING

The miners work in teams of five or six, known as communal artisanal miners (CAMs), in a pit at Baken demarcated for artisanal diggers. There are over 20 CAMs working the concession, which is no longer suitable for mechanized operations, but still contains diamonds that can be unearthed with a pick and shovel. By reinvesting their profits, most CAMs have bought motorized drills to break up the hard rock, as well as other equipment that eases their workload. Some miners have acquired a small truck to manage the arduous gravel road they travel each day to the site. The project services four communities in the surrounding area.

Katleen, a CAM team leader, explains she’s putting bread on the table for five dependents and their families. The biggest recovery her team has unearthed was a 12-carater, she recalls with an air of excitement and hope that the feat can be repeated, even if it has been about a month since they uncovered their last stone.

“We don’t find diamonds every day, but when we do, many people benefit,” she says. “Even if it’s a small amount, it all helps.”

(Avi Krawitz)

Kimberlites and rivers

LOR believes its CAM project can serve as a model of collaboration between mine owners and the communities in which they operate, providing employment, skills, and sustenance opportunities in areas where such prospects are scarce.

Baken covers an area of 41,334 hectares on which around 10 junior miners work concessions in formal mining that is separate to the CAMs. LOR centralizes much of the admin and regulatory work for the different operations and aggregates and sells the goods on their behalf. That helps reduce the bureaucracy and costs that inhibit many junior miners around the country.

The operation is located on South Africa’s west coast near the border of Namibia; an arid area of “ugly beauty,” as one of the locals put it, famous for its desert daisies and its wild cold Atlantic Ocean coastline.

It’s equally famous for its diamonds, an area where De Beers operated in the past, and where government-owned Alexkor manages its operations over a vast space adjacent to Baken, ranging from mechanized alluvial deposits, more risky beach mining, shallow-water mining and deeper marine mining — all operated by various concession holders. Not far away, across the border, are De Beers’ Namibia projects.

The area gained an almost mythical status given its location around the mouth of the Orange River, where the river meets the sea. Diamonds have traveled that distance over millions of years from various famous kimberlites via volcanic eruptions that burst into the atmosphere.

In fact, diamonds at alluvial mines in the area were carried there by three rivers that sourced from different kimberlites, explains Lyndon de Meillon, a diamond entrepreneur and geologist with interests in alluvial mining projects along the Middle Orange River as well as with Pioneer Diamond Tender House.

RELATED READING

Those include the Riet River, which drains diamonds from the Koffiefontein and Jagersfontein kimberlites. Eruptions from the kimberlites in Kimberley contributed to the alluvial deposits along the Vaal River, and the Lesotho kimberlites — Letšeng and Kao among them — fed into the deposits along the Orange before its point of confluence with the Vaal. Beyond the point where the rivers meet, further northward — such as at Baken — the Orange contains a mix of stones from the three rivers.

“You have a unique situation in which you have six or seven world-class kimberlites within the drainage of these three rivers,” de Meillon explains. “If you look at the populations of diamonds in these three rivers, there are clear differences and changes in value, which tells you they come from different kimberlites.”

Production from the Middle Orange River, which is before the confluence, is known to yield some of the highest-quality and valuable diamonds in the market, de Meillon reports. A 29.52-carat pink diamond recovered from the area sold at a tender by Pioneer in Johannesburg last year for $8 million. Beyond the point of convergence, where there is a mix of kimberlite sources, the diamonds have a lower value.

(Pioneer Diamond Tender House)

100 years of mining

Perhaps more importantly, geological estimates suggest there are still substantial volumes of diamonds in these alluvial deposits. That is despite the maturity of mining in the area. De Meillon believes there is potentially another 100 years of alluvial activity that can take place there at a rate of around 300,000 carats a year.

But fulfilling this potential would require the right economic and regulatory environment, he insists. Such conditions are not taking shape in South Africa, members of the South African Diamond Producers Organisation (SADPO) noted in panel discussions at the Kimberley International Diamond Symposium (KIDS), which took place in Kimberley in late August.

SADPO and its constituents of junior and small-scale miners note their difficulty in navigating the regulatory environment. In addition to the lengthy process required to attain or renew various licenses, the regulations also entail additional costs, says de Meillon, who serves as vice president of SADPO.

He estimates that the cost of compliance for a small operator adds about 7% to the production expenses. “Add to that the 5% export levy on rough diamonds and you’re down 12% before you even start mining,” de Meillon notes. “That’s totally crazy.”

While the diamond sector has its own challenges and considerations, South Africa’s mineral policy takes a broader approach to address the concerns of the mining industry as a whole. Policy is focused on the bigger conglomerates and larger sectors such as gold, platinum, and iron ore and is also expected to apply to the small-scale diamond sector, which has unique requirements, stresses John Bristow, a veteran diamond-mining consultant.

Bristow also points to factors such as the lack of reliable electricity supply in South Africa, which plays a role in raising costs for miners, impacts efficiency and reduces confidence to invest in the sector.

Those considerations have combined with the weaker global diamond market to put pressure on the country’s small-scale miners. The drop in rough prices in the past year has meant that lower-value operations have become less economically viable.

RELATED READING

“We’ve got to get through the next six months as prices are dropping,” de Meillon warned in an interview in October. “But there are those who can’t survive and they will be gone. It’s a big issue; we’re going to see big problems in Africa and globally.”

His dire predictions have started to come true. One or two operations were put on care and maintenance in December and January, including at the Helam fissure mine, where some 350 people were employed, reports Bristow.

Untapped potential

There is an upside if the country can change the regulatory environment, ensure a quicker licensing process, and provide reliable electricity, Bristow stresses. In addition, the application of new technology that is available today, such as specialized X-ray capabilities to avoid stone breakage, means that some of the projects that were previously deemed uneconomical may be revived, Bristow reassures.

Along with the potential to attract investment, the mining executives at SADPO’s KIDS symposium stressed that the small-scale mining sector could stimulate employment in areas that most need it.

The Northern Cape, the province through which the Orange River meanders after the confluence, has an unemployment rate of 22.1%, according to Statistics South Africa, which is admittedly better than the national average of 32.7%. However, many of the mining operations are in remote locations and rural areas where unemployment is at 50% and can reach as high as 80%, according to research the Africa Earth Observatory Network (AEON) published in partnership with Nelson Mandela University in 2021.

The paper, titled “Status of the South African Small and Junior Diamond Mining Sector,” highlighted the decline of the industry over the past two decades. In 2004, the segment consisted of 2,000 companies employing 25,000 people, whereas in 2020 it had just 220 entities with 5,720 employees, the paper noted.

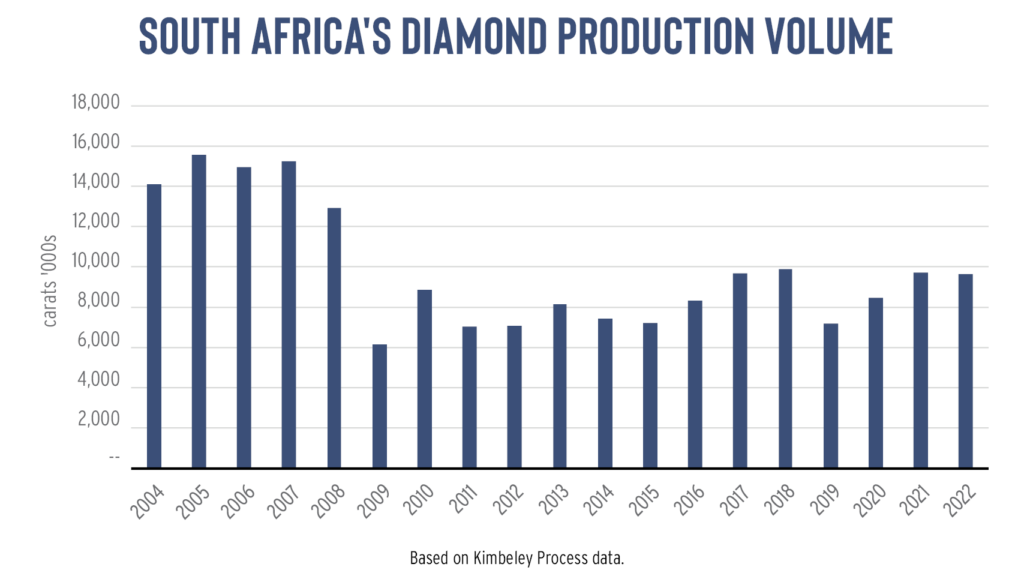

“The sector previously produced 300,000 carats per year valued at ZAR 4.2 billion [$222 million], but the industry faces declining production and revenue trends,” the authors stressed. The situation is highlighted by the decline in South Africa’s overall diamond production, which has dwindled as its large kimberlite operations have closed or become less lucrative. The country’s diamond production fell from 15.56 million carats in 2004 to 9.66 million carats in 2022, according to Kimberley Process data.

While no new major mines appear to be on the horizon, SADPO and others believe the small-scale miners can make a positive contribution.

“This important small mining sector faces considerable challenges and further decline unless its potential contributions in respect of the exceptional quality of its diamond production, financial contributions, and job-creation benefits are recognized and supported, and enabling mineral and mining policy is introduced as a priority,” the AEON researchers concluded.

Illegal miners

A focused approach would also help bring many informal miners into a more structured employment or entrepreneurial realm. In the absence of employment, informal miners from the rural areas converge on the many abandoned mining sites scattered around South Africa. While this has mainly affected the gold sector, diamonds are not immune.

Thousands of illegal miners — known in South Africa as Zama Zamas — descended last year on an almost deserted smalltown called Kleinzee in the Northern Cape, where De Beers had previously operated. The two main concerns for these miners are that they typically sell their goods on the black market, below market value, and the more obvious safety issues. In August, 13 miners were killed when a tunnel collapsed, the South African Broadcasting Corporation (SABC) reported.

SADPO believes investments in small-scale operations could enable the mines to entice locals away from illegal activity and provide them with employment or mining opportunities such as within the CAM program at Baken. The miners also become educated in responsible mining practice. At Baken, for example, the CAMs have a safety meeting at the beginning of each day, Coetzee notes.

There are other scattered attempts to provide artisanal miners with a formal structure at South Africa’s aged and abandoned diamond sites. In Kimberley, workers are given permits to work their way through the soil across vast areas predominantly owned by Ekapa Mining.

People first

Around 2007, the artisanal mining operations in Kimberley were marred by violence among the miners — who were at the time illegal — and between miners and law enforcement. By 2015, the miners were encouraged to organize into cooperatives, allowing them to gain permits to mine land provided by Ekapa. The company had bought the Kimberley mining operations from Petra Diamonds, which had previously acquired them from De Beers.

The largest of the cooperatives, Batho Pele, has 800 card-carrying members and about 1,200 non-card-carrying ones on its database, says Rasta, a charismatic operator who is one of seven directors of Batho Pele.

The members take their production to Batho Pele’s sales office in downtown Kimberley — around the corner from De Beers’ iconic former headquarters overlooking the town’s Big Hole landmark. The cooperative works with CS Diamonds, a local tender house, to sell the goods.

“When we were illegal, we were selling on the black market, under the trees,” Rasta notes. “Now, our members find a diamond and bring it to us and get a valuation, and we take it to CS Diamond, which gives them insurance. And when the stone is bought, they have a say in the sale.”

While production at the cooperative is comparatively low — 300 carats is a “beautiful month” — notes Rasta, the system at least attempts to provide miners with a fair price. An 8.77-carat rough stone sold for ZAR 1.8 million ($95,000) at the time of Rapaport’s interview with Rasta. Batho Pele takes a 2% commission as the concession holder, while CS Diamonds also takes a small cut.

The system has allowed Batho Pele to grow, and it has now applied for a small-scale mining concession along the Orange River.

But trust is an issue, and some miners at one of the Batho Pele sites, informally known as Beefeater given its proximity to a factory of that name, expressed doubt about where to sell their stones — that is, if they found any. The miners appear despondent about their lack of success, most going months on end without any luck.

Beyond simple survival, their ultimate goal is to raise their status, perhaps advance their standing in the industry and make a positive contribution to their country.

The barriers to such opportunities are similar to those faced by the small-scale miners, with the lengthy and costly process of applying for mining permits also blocking development among artisanal miners.

“This situation whereby a 5-hectare mining permit takes as long as 13 months is untenable, and for an emerging honest historically disadvantaged South African small-scale miner is unaffordable and unacceptable,” the AOEN report stated. “This situation is one of the key reasons and drivers for the burgeoning illegal and unmanaged artisanal and Zama Zama mining growth in all commodities across South Africa.”

The SADPO mining executives share the frustration. The industry can play a role in reducing the illegal mining activity in the country by involving the local population with employment, skills development, and community upliftment, de Meillon notes. But it requires support from the government to ensure the longevity of the trade.

“It’s a relatively small industry when you consider South Africa’s full spectrum of mining, so the 350,000 carats from alluvial diamond mining may be a lower priority for the government,” he stresses. “But if you think about jobs, 20,000 jobs are a lot of jobs, especially in the rural areas, and yet there’s no effort to solve these issues.”

He concludes: “We know what is wrong with the legislation, and we’re trying to get the message across to government, with very little success at this stage.”

RELATED READING

Main image: David Polak/midjourney

Stay up to date by signing up for our diamond and jewelry industry news and analysis.