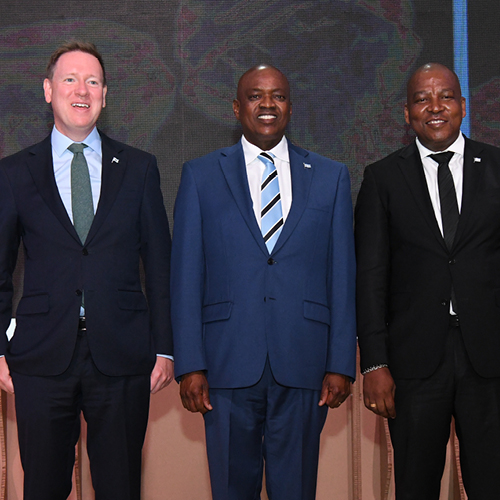

Botswana President Mokgweetsi Masisi paused for a moment after stepping up to the podium to address the annual Natural Diamond Summit in Gaborone.

As he looked through the marquee venue, aptly known as the Diamond Dome, with its intentionally earthy décor, Masisi appeared measured. The speech he was about to give was his first major address to a broader De Beers-organized audience since the government announced its landmark deal with the company on June 30.

His words would highlight the government’s unique partnership with De Beers, after the prolonged negotiations tested the relationship. Masisi would demonstrate confidence in the natural-diamond industry, which has endured a difficult year in 2023 but remains vital to Botswana’s economic development. And that would tie into the Botswana-De Beers narrative that a focus on sustainability would drive growth — relating to how the country and the industry connect “people, planet and product,” the theme of the summit.

“We’ve already made strides in the direction of sustainable partnerships and collaborations where industry players, government and communities are working together to unlock the full potential of our precious resource,” Masisi said. De Beers CEO Al Cook conveyed a similar message at the summit, which took place from November 13 to 14.

Economic reliance

Botswana still depends on diamonds for economic growth, despite efforts to diversify the economy away from mining.

The economy is expected to grow only 3.8% in 2023, compared to 5.8% in 2022, due to weak demand for rough diamonds, Masisi said in his State of the Nation Address on November 6. That rate signals a normalization of the economy after the ups and downs of the pandemic period, notes local economist Keith Jefferis, managing director at eConsult Botswana.

Commodities from the mineral sector, particularly diamonds, copper-nickel, and silver, accounted for 92% of total exports, Masisi added. Diamond mining accounted for approximately 20% of gross domestic product (GDP) in 2022, while diamond cutting, polishing, and trading made up about 5%, reports Jefferis.

While that reliance on diamonds is a concern for the country, the government’s successful allocation of its revenues has made Botswana an example of the positive impact diamonds can have on society.

“We’ve been able to transform our economy and by extension support livelihoods predominantly through the discovery of diamonds, but more importantly the prudent management of these shining and rare valuable stones,” Masisi told the summit.

In 2011, the government established a fiscal rule whereby 40% of mineral revenue would be saved in the form of financial assets for future generations, while the rest would be invested in infrastructure and human capital development, he noted. Through such people-centric economic planning, infrastructure development, education, health care, and social support are available as a basic human right to all citizens, Masisi stressed.

RELATED READING

The De Beers contribution

Many point to De Beers’ role in facilitating that.

The company has been operating in Botswana for over 50 years, and in the last decade made Gaborone its main distribution hub. De Beers moved its aggregation and sales operations from London to Gaborone as part of its previous sales agreement with the government, signed in 2011. That deal also saw the miner earmark more rough for local beneficiation, thus incentivizing sightholders to open factories in the country, as well as the establishment of Okavango Diamond Company (ODC) to conduct independent rough sales on behalf of the government.

Botswana also benefits from the unique ownership structure of De Beers in that 80.8% of the company’s income goes to the government, Jefferis points out. The country owns 15% of the company, with Anglo American holding the rest, while De Beers and the government have an equal stake in mining company Debswana as well as in DTC Botswana (DTCB), which sorts and values all of Debswana’s production.

In terms of the internal accounting, Debswana recovers the rough and sells it to DTCB, which sorts the goods for its two clients: De Beers Global Sightholder Sales (GSS) and ODC, which then sell to their respective customers.

The government gains taxes, royalties and dividends from those various transactions, entities, and sales channels, Jefferis explains.

(De Beers)

The new deal

The stakes were therefore understandably high as the government and De Beers negotiated a new 10-year sales contract and 25-year mining license for Debswana. They had to seek measures that would bring additional value to a now-maturing local industry. The deals were scheduled for 2020 but were postponed during Covid-19 and prolonged another two years due to reported sticking points in the discussions.

Speaking at the summit, Masisi and Cook expressed confidence the agreement they forged would prove to be a game changer for the country and the industry.

“The government of Botswana and De Beers Group have entered into an historic agreement which is guaranteed to transform Botswana’s diamond story, showcasing an unwavering partnership that champions sustainable economic progress,” Masisi said.

The deal, which has yet to be finalized, has four major components and several subplots.

RELATED READING

1. Production promise

The first of those parts is the renewal of the 25-year mining lease governing Debswana’s activities. The mining company recovered 18.57 million carats in the first nine months of 2023 from its four mines — Jwaneng, Orapa, Letlhakane and Damtshaa. That accounted for 78% of De Beers’ total production, with its operations in South Africa, Namibia and Canada making up the rest.

Having the mining leases in place clears the way for shareholders, including De Beers’ parent Anglo American, to make important development and investment decisions for those operations. The most important project in the foreseeable future will be the expansion of Jwaneng to underground operations.

Historically dubbed “The Prince of Mines,” and recently upgraded to “The King,” Jwaneng is considered the world’s richest mine by production value. The underground deposit, which was approved in 2021 at an estimated cost of $6 billion, will start producing ore in 2033. By then the open pit will have sunk to a depth of 894 meters from its current level of about 500 meters, noted mine management in a visit to the operation during the summit. The pit is 2.7 kilometers long and 1.7 kilometers wide.

Debswana is currently mining the cut-8 section and stripping waste in preparation for cut-9; a cut referring to a widening of the pit to reach a broader and deeper section of the kimberlite ore. Cut-9 ore production is on track to begin in 2027 and sustain the operation through the transition to underground mining, which will potentially extend the mine’s life beyond 2050, its management said.

Securing the mining licenses will enable De Beers, Anglo American and the government to take on further expansion projects across the De Beers portfolio.

2. Empowering Okavango

With future production guaranteed, the 10-year sales deal seeks to maximize revenue for the government from all those diamonds.

That agreement will see parastatal ODC steadily up its share of Debswana’s production from 25% to 30% in the coming months, and then to 40% and eventually 50% over the next decade. Given Debswana’s current production, ODC will be entitled to between an estimated 7 million and 12 million carats per year, which will elevate it to a top-tier rough-diamond supplier.

ODC is planning to change its sales and marketing strategy accordingly, as managing director Mmetla Masire explained in a recent interview with Rapaport Magazine. That will likely include the introduction of contract sales to complement its auctions, and an initiative to brand Botswana diamonds, he elaborated.

RELATED READING

3. The beneficiation challenge

Meanwhile, as Debswana provides more goods to ODC, De Beers will be left with fewer rough diamonds to supply its sightholders — many of which recently set up factories in Gaborone with the goal, or promise, of receiving De Beers supply.

The number of diamond-cutting and polishing companies operating in the country has doubled in the past two years, from 23 to 46, Masisi reported in his state of the union address. This increased employment in the sector from 2,207 to 4,239 during that period, he added.

However, the volume of rough available from De Beers has not increased, members of the Botswana Diamond Manufacturers Association (BDMA) noted in a forum with this journalist.

De Beers changed the makeup of its boxes in 2021, a move manufacturers speculate encourages people to polish more smaller goods in Botswana. They point to the “typical Botswana box,” which used to contain a range of 2.5- to 4-carat rough, but today consists of 2 to 4 carats.

De Beers insists it is focused on creating box assortments that “will best meet the needs of sightholders, both within the beneficiation space and across the broader supply landscape,” a De Beers spokesperson explained in an email.

Shifting to smaller stones means cutters can make more pieces but with fewer carats, BDMA members claimed. “You need to employ more people, increase your infrastructure, have more machines…everything must increase to polish the same amount of goods,” explained one executive who requested anonymity. “So, your carat output remains, but your workforce must increase in order to beneficiate those goods in Botswana.”

(Okavango Diamond Company)

High-cost manufacturing

Still, manufacturers believe the change is putting additional pressure on the manufacturing sector as the cost of production in Botswana is high relative to other centers. Among the additional costs manufacturers are required to pay is a training levy, which was recently reapplied to the diamond sector.

The levy is currently set at 0.2% of turnover, and the BDMA is urging the government either to reduce the rate or base it on a company’s wage bill. In the petroleum industry, the charge is 0.05% of turnover, given the low margins in that sector.

“We’re lobbying government for the same,” says BDMA chairman Siddarth Gothi. “We’re an industry with high turnover, thin margins, and low profits, so it puts us at a disadvantage to pay this training levy based on turnover.”

This charge adds to the cost of manufacturing and beneficiating in Botswana relative to other centers such as India and neighboring South Africa and Namibia, Gothi adds.

Skills deficit

The sudden increase in factories operating in Botswana has also raised competition for skilled workers. That was especially the case during the initial influx in 2022 when the diamond market was still relatively strong, notes Gothi. Companies lost their best employees to the new entrants and were left with no choice but to train fresh talent, which in turn adds to the cost of production of the established factories, he asserts.

Those skills are not easy to replace, Gothi stresses. “There’s not enough talent and there can also be challenges getting visas for expats,” he adds. Companies must keep a ratio of one expat for every three Batswana locals it employs.

While that movement of workers stabilized as the market slowed in 2023, manufacturers still had to replace the skills they lost even in the current difficult market conditions. The BDMA is working to ensure that its members get assistance from the government to mitigate the effects of this situation, Gothi reports.

Jewelry focus

Skills development and job creation are among the core goals of the new agreement, De Beers’ Cook stressed. “It can create tens of thousands of new jobs in Botswana,” he assured the summit audience.

Cook also hinted to an extension of the country’s beneficiation program. While that effort has historically focused on advancing the diamond-cutting and polishing sector, De Beers is now increasing beneficiation “to establish Botswana as a natural jewelry-manufacturing center,” he said.

De Beers will establish a joint venture with one of its sightholders or another partner to create scale jewelry manufacturing that spans the entire value chain, explains the De Beers spokesperson. That includes polishing, jewelry design and manufacturing through to international retail marketing and distribution, he adds.

Masisi believes the increase of supply through ODC will “fast-track the beneficiation for cutting, polishing and manufacturing of jewelry locally,” he said in the state of the nation address. “Our strategy is to increasingly expand diamond jewelry consignments to more markets around the world.”

4. Diamonds for development

All that is part of the broader aim to accelerate Botswana’s economic diversification. To that end, the agreement also facilitates the creation of the Diamonds for Development Fund, whose goal will be to add value to the Botswana economy.

De Beers will contribute BWP 1 billion ($75 million) to the fund up front, and up to BWP 10 billion ($750 million) over the next decade. The fund will identify sectors beyond the diamond value chain that support the government’s national development plan, the fund’s website explains.

Cook expects it will be the most enduring and impactful part of the new agreement. At the end of the day, he emphasized, the deal aimed to support the vision of the government’s goal “to look beyond mining and beyond natural resources to grow sustainably the prosperity of the people of Botswana for decades to come.”

By doing so, Botswana can be a catalyst for development across the diamond industry, Cook highlighted.

“While Botswana’s diamond dream has been built by diamonds over decades, in the future the global diamond dream will be built by Botswana,” he stressed. “The strong foundations of Botswana will underpin that evolution and its evolution to become the world’s most important diamond nation.”

RELATED READING

Brands Still Have a Long Way to Go in Their Sustainability Quest

Main image: David Polak & Elisé Jurkovic.

Stay up to date by signing up for our diamond and jewelry industry news and analysis.